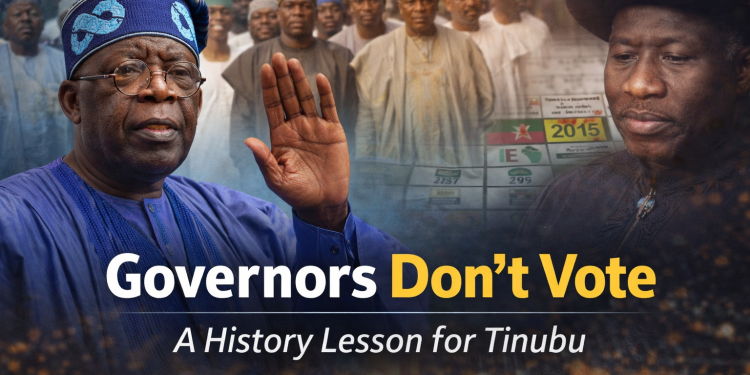

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu currently leads a party that governs the vast majority of Nigeria’s states. For some political strategists, this numerical strength is viewed as a major electoral advantage. For others, however, Nigeria’s political history offers a cautionary tale.

Political dominance at the state level has long been considered a strategic asset in Nigerian elections. Yet past outcomes suggest that control of governorships does not automatically translate into victory at the presidential polls.

As Nigeria’s political landscape continues to evolve ahead of the next general election, the growing dominance of the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) at the state level has reignited debate over whether institutional strength can reliably convert into nationwide electoral success.

The Jonathan Precedent

In 2015, then-President Goodluck Jonathan entered the election as an incumbent with significant institutional backing. At the time, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) controlled approximately 29 state governments across the federation.

Despite this advantage, Jonathan lost the election to Muhammadu Buhari, the APC candidate, in what became Nigeria’s first peaceful transfer of power from a ruling party to an opposition party.

The outcome underscored a fundamental principle of democratic politics: governors do not vote on behalf of citizens.

Numbers vs. Voters

Political analysts note that while governors can influence party organization, campaign logistics, and voter mobilization, presidential elections are ultimately decided by voters — not officeholders. Public perception, economic conditions, security concerns, voter turnout, and regional sentiment often outweigh party dominance at the state level.

Nigeria’s constitution further reinforces this reality, requiring presidential candidates not only to secure the highest number of votes nationwide, but also at least 25 percent of the vote in two-thirds of the states, making broad-based national appeal essential.

“The assumption that governors automatically deliver their states has repeatedly proven unreliable,” one analyst observed. “Voters often make different choices at the presidential level than they do in state elections.”

A Warning, Not a Prediction

The comparison to 2015 is not a forecast of defeat, but a reminder that political power remains fluid. Public confidence, policy performance, and the national mood continue to play decisive roles in election outcomes.

For President Tinubu and the APC, the lesson from Jonathan’s experience is clear: numerical dominance does not substitute for popular legitimacy. Electoral success depends less on how many governors a party controls and more on whether voters believe their lives and prospects are improving.

The Road Ahead

As Nigeria approaches another election cycle, the central challenge for the ruling party will be converting institutional strength into genuine public support. History suggests that overlooking voter sentiment in favor of political arithmetic can prove costly.

The 2015 election remains a defining reference point — a reminder that in Nigeria’s democracy, ultimate authority rests with the people, not with governors.

This article is part of our ongoing political analysis series examining Nigeria’s evolving democratic landscape.